Over the past year, Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) has amassed over 20.4K followers, becoming one of the most beloved accounts on a certain corner of twitter.

Rebecca Brill, the woman behind the action, first fell in love with Plath as a teenager, counting herself among the many female literary types who turned to The Bell Jar in times of adolescent turmoil. I was lucky enough to speak with her about how what it’s like running the account, and what it’s taught her about literature’s favorite enigma.

We begin by agreeing we don’t know a single woman who hasn’t had an absolutely demented relationship with food at some point in their lives. To try to characterize Plath’s habits as normal or abnormal, healthy or obsessive, seems to be a futile, and arguably invasive, pursuit. If anything, the more one learns about what Plath ate and, more significantly, how Plath documented what she ate, the more questions one has.

Brill was moved to start this account for a number of reasons. The food diary was, at least in part, borne of a self-soothing habit of transcription. “It’s just something I do when I’m stressed in my own writing,” she says. “I just type other writer’s work in general and I think it helps you feel connected to them in a way, like I’m writing exactly what Sylvia Plath wrote so a part of me is Sylvia Plath.” One might also deduce from the old “you are what you eat” adage that if they could eat like Plath, perhaps they could write like her — popular articles titled “how to eat like your favorite authors” imply such a connection.

Embarking on this project at the start of lockdown, Brill was looking for something to do that could be both active and passive at once, or what she describes as “soothing in a mind-numbing way.” Scanning Plath’s texts for alimentary buzzwords — a process she calls a “mental highlighting” — she found a kind of escape from the chaos occurring off the page.

Both of Brill’s accounts are projects of research, transcription, and ultimately of curation. Plath did not keep a food diary, per se; she kept a diary, or journal, in which food was often mentioned. In extracting these instances from their original context and posting them in sequence as she does, Brill — aided by the list-like quality borne of Twitter’s limited word count and eternal scroll feature — reassembles these excerpts into a bonafide, if manufactured, food log.

While @whatsylviaate is of course limited to food-related musings, Brill’s Susan Sontag account excerpts content of all sorts from the Against Interpretation writer’s journals. As someone burdened (or blessed) with a food-centric brain, it seems only natural to me that she would search Plath’s journals for what she ate, but I know this isn’t an obvious choice to everyone. When I asked her why she imposed this additional constraint when considering Plath, she notes the association most people have with Plath and the kitchen, explaining that she was motivated to re-contextualize this space as a site of joy and comfort for Plath, as it was through much of her life. “It’s important to me for even people who don’t care about Sylvia Plath to know that she was a complicated person who did a lot of things besides stick her head in an oven,” she says.

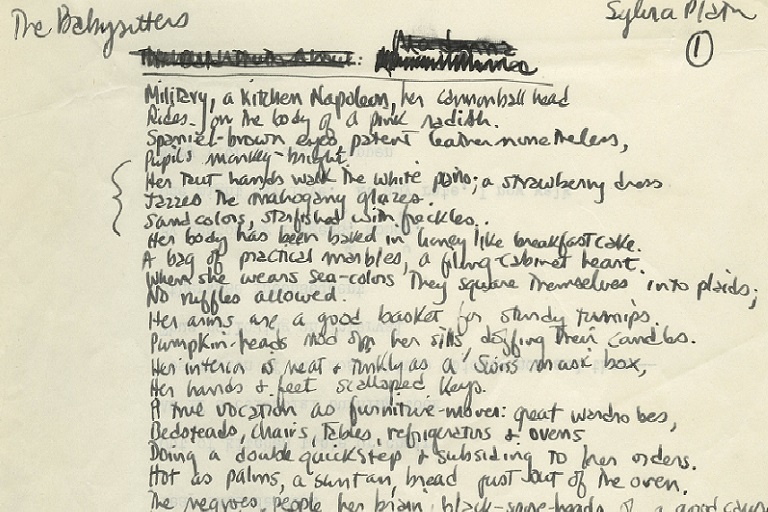

If you’re wondering how much of the complexity of Plath’s character could be revealed through what she ate for lunch, then you probably haven’t taken a good look at Brill’s account. Far from providing simple sustenance, food offered Plath a means of expressing — and sometimes obscuring — her innermost feelings. In this way, her descriptions of food can simply not be extricated from her thoughts on other matters. Tacking adjectives like “brooding” and “monstrous” before ordinary food items like “soup lunch” and “bread pudding,” respectively, Plath animates and assigns various moods to what she eats, often to a subtly comic effect. From the reticent “Tom brings me juice” to the impassioned “listen to these two outrageous menus and be rightfully indignant […] starches! starches!” her tone might indicate how she feels about what’s on her plate but, even more so, it tells a whole story about her emotional state at that moment — both of writing and of eating.

“The way she’ll describe food is so poetic because it’s not just about food, it’s about everything else going on,” says Brill. You can track the ebbs and flows of Plath’s relationship with Ted, she notes, through the way she describes their meals together. While their early repasts are described with soft and complimentary adjectives, moments of tension between the two are crystallized through Plath’s recollections of what they ate and drank. When he makes coffee, she describes the resulting beverage as “poisonous brew.” Something about their relationship has turned bitter and venomous; unswallowable.

Brill’s quotes come not just from Plath’s journals, however, but from her letters as well, and while the distinction between the private and public doesn’t quite come through on twitter, Brill herself has taken note of the ways in which Plath fashions food descriptions differently when she’s cognizant of an audience, even if its just an audience of one. “She writes about food really brightly sometimes when talking to her mom and it seems that’s almost a mechanism to conceal the less pleasant things that are happening in her personal life or with her mental health,” Brill notes. “I don’t think, for example, if she says to her mom, ‘omelettes are delicious,’ that that’s a lie but I do think it’ a way to obfuscate important information about her mental state or her marriage to Todd. A lot of times she just goes on and on about cooking at the expense of other things.” Interpersonally, food becomes a kind of crutch for Plath, convenient material for an epistolary diversion. In her private writings, however, it is something of a delicious secret, one of which she can not get enough. “It’s kind of perfect, though,” laughs Brill. “if you’re really trying to avoid talking about something you can just start talking about what you’re eating.” This seems right: sharing what one eats can be deeply personal, but it can also be a tactic for dodging unpleasant truths, like a proffering of one kind of intimacy to avoid another, more perilous kind.

From a breakfast of “2 doughnuts, a hamburg, a glass of milk & a cup of coffee,” to “three wonderful slabs of cheese…a gooey ripe brie, a superbly mouldy blue stilton & a fat round of Wensleydale,” Plath demonstrated a proclivity for the decadent. On more than one occasion, she mentions that she has drank six cups of milk in one meal, with one account even bringing the record up to seven cups. The quote tweets formed a chorus of disbelief.

Brill’s account has also managed to reach another sector of Twitter, however, one too preoccupied with nutritional content to register emotions like disgust or disbelief. Last summer, she started to notice a cropping of shares and likes from young women who seemed to exist on the margins of the pro-ana twitter community. With anonymous avatars and bios describing themselves as “vent” accounts — a term indicating they don’t wish to promote anorexia, but rather to indeed vent about their struggles, even if that means sharing things like weight, calories and wishes to be smaller — these accounts took a sudden interest in Brill’s account, speculating over how many calories Plath might have been eating. Neither decisively pro-anorexia or pro-recovery, these anonymous food diarists exist in a kind of in-between space. “I’m really interested in that truly ambiguous morality around food and documenting it,” says Brill.

It seems that it was only a matter of time before a community like this got their hands on the account. Despite the fact that there is no real evidence Plath suffered from anorexia or any other kind of eating disorder, fans and foes of the poet have been making posthumous diagnoses for decades. The only incidence that might suggest Plath struggled in this way is when she records burying a hot dog in the sand when no one was looking — but again, Brill interprets this more as an exhibit of Plath’s eccentricity than evidence of genuine food avoidance. It’s certainly not substantive enough to justify the curiously widespread assumption that Plath was anorexic. Brill instead attributes this phenomenon to the writer’s reputation as a waifish depressive. “She’s this poster child for female depression, and depression is often associated with eating disorders, and anorexia in particular,” says Brill. Perhaps female sadness is irrevocably conflated with an at least aspirational disembodiment; the same might be said of female genius, with which Plath has become synonymous. For some, reading Plath talk so passionately about such rich, indulgent foods comes as a shock. The tortured genius, we assume, is also the starving poet, un-encumbering herself of flesh so she can emerge a purely intellectual, spiritual being.

Of course, Plath’s impulse to document so much of what she ate certainly indicates some level of fixation with food. When she writes self-deprecations like “at lunch I stuffed myself like a hog,” it’s unclear whether she is simply being playful about her perceived indulgence or expressing genuine shame over it. Brill shares that her mom is appalled by many of the posts, and “just super convinced that Plath is a bulimic just based on the quantity of food that she ate.” Though many feel the same way, Brill herself doesn’t have the same suspicion, characterizing Plath’s intake as indeed “abundant” but “not crazy or necessarily bingey.” Ultimately, she argues, it comes down to the fact that Plath was skinny; no one could believe she was eating all that food and really keeping it down. “Plath is conventionally attractive and skinny,” Brill states. “Everyone loves, like, that picture of her on the beach in the bathing suit.” Everyone does love it; this image of a literary Marilyn Monroe, symbolizing the sexual and cerebral all at once, titillates the public. And the image of that same pin-up of American poetry scarfing down fresh bread and meat, chocolate pudding and apple cake and all kinds of decadent confections, excites us even more. “When she’s eating all this food with relish and joy — it’s something we might not celebrate if Plath was fat,” says Brill. “And I think I'd be remiss not to say that maybe part of why it’s compelling to people to watch Sylvia Plath eat is because it feels divorced from her body.”

Accused, on a few occasions, of romanticizing Plath’s depression by broadcasting her so-called “depression meals” for entertainment, Brill mantains is that she is open to these criticisms but doesn’t, ultimately, believe that’s what she is doing. “I am making an editorial choice by removing the food descriptions from their context,” she acknowledges. “But just because I’m putting it on twitter does that mean I’m romanticizing it? […] I’m not sure you can even differentiate what is a ‘depression meal’ for Plath from what is simply a strange concoction she took genuine joy in putting together.” Indeed, she argues that it is Plath’s lack of reservation about delving into the abject side of eating that makes her food writings so compelling. “The stuff that she eats by herself is, like, a little bit gross or abject or smelly — like, I don’t know, liver sandwiches,” says Brill.” I just love knowing about the kind of strange concoctions which are not for company but just so private and personal and a kind of pure bliss…it’s that leap [from the pleasant to the abject, the aesthetically perfect to the dangerously messy] that I guess separates something nice from, like, something genius.”

Brill also figures that, aside from the poetic side of things, “there is just a sector of people that just want to know what other people are eating.” After a moment’s pause, she adds that she herself probably belongs to that cohort. Who, I dare ask, doesn’t? There is a unique intimacy to seeing what other people put into their mouths, one that is heightened when the eater doesn’t know they’re being watched (or read) — in some ways, it is the ultimate form of voyeurism. It’s no wonder that the food diary genre has become a prolific - and profitable — one, from the quotidian shopping list to pro-ana twitter to the trend of “what I eat in a day” videos on youtube and TikTok. Though she lives primarily on “cheerios and string cheese,” Brill finds herself fascinated by other people’s eating habits, citing Grimes’s unhinged food diary video for Harper’s Bazaar as one of her all-time favorites. It is not cooking, then, and perhaps not even eating, to which Brill is most powerfully drawn, but rather to the unlikely connection that can form between strangers simply from getting a glimpse into what the other has eaten. While a lot of the “what I eat in a day” type content is centered around dieting and restriction, which doesn’t appeal to Brill, she find herself returning time and again to the kinds of videos and blogs that document the everyday eating habits of everyday people. As it turns out, it’s not only literary icons whose diets we long to unveil, but also those of random strangers.

Much of Plath’s accounts of what she ate revolve around the who, what and where of the meal. Brill also takes notes of how Plath seems to vacillate from states of deprivation to states of indulgence, dipping her toes into luxury then retreating again. “It’s kind of weird because sometimes she can’t really afford delicious foods but then she’s like having dinner at Auden’s and shipping champagne,” she says. “Or she doesn’t eat at the fancy restaurant that her fancy friends go to because she can’t afford it, but then she’ll compensate later with a bunch of lamb chops. She ultimately has access to these spheres of, I don’t know, elitism or fancies.” Ultimately, that one eats has everything to do with their social standing. To dine in company also means to be included, to have a seat at the (literal) table, to share in the banquet that is life. Her invitations to W.H. Auden’s, which seem to appeal to her mainly for the endless quantities of champagne they provide, also draw her into certain circles. In draining Auden of his champagne, Plath asserts her right to be present, to take part in the festivities.

“It’s so easy to mythologize her,” says Brill as our conversation draws to a close. “Number one because she’s such a genius but number two because she just has that mystique around her that we were talking about, that just gets borne out of the fact that she died young, and beautiful, and a genius.” Premature death can indeed keep one immortalized as a mystery, before the years have robbed them of their mystique — in our youth-obsessed culture, the loss of such beauty often means the displacement of intrigue with irrelevance. With @whatsylviaate, Brill aims to complicate rather than reinforce the image many of us may have of Plath. For many, she believes, the account serves as an inspiration to find some element of the sacred in the everyday. “I think that it hits a nerve with some other people that with the very language Plath uses she really elevates the mundane into something really beautiful and theatrical,” she says. “She uses the same heightened language to describe, like, her lunch as she does in her poetry to describe depression or love or sex. And eating does become as interesting as death or love or sex. To some people I guess it already is.”

***

Julie Goldberg is a writer of fiction and essays. Her work can be found in Hobart, The Los Angeles Review, Tablet and more. She is the editor-in-chief of NOSH.